George Steevens – a rather ‘complex’ man

(a new memorial in the Lady Chapel commemorates this former Hampstead resident)

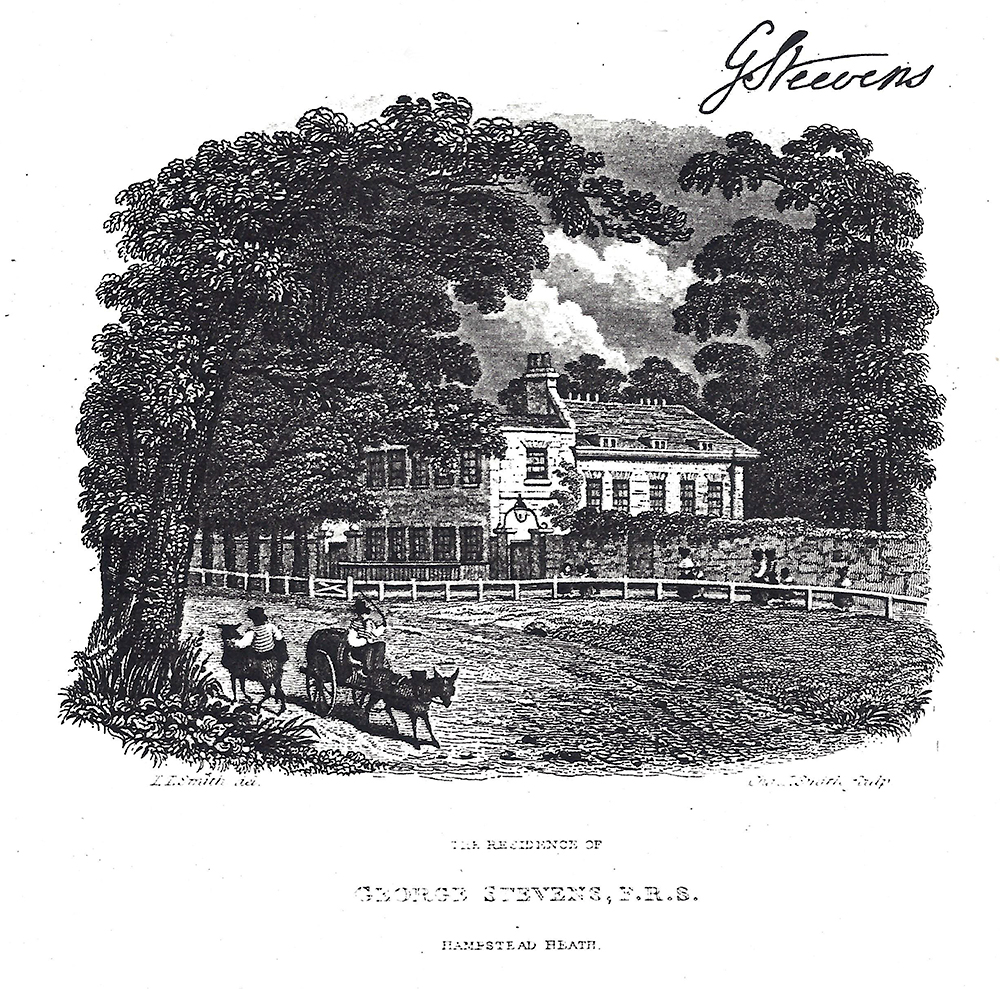

George Steevens (1736-1800), educated at Eton and King’s College, Cambridge, inherited a competence and a substantial house in Poplar from his father, a former ship’s captain and Director of the East India Company. He preferred to live in Hampstead, where he bought a house, formerly a tavern named the Upper Flask. His daily routine was to walk into London before 7 am, paying visits to friends, bookshops, and publishing offices before walking home in the early afternoon to pursue his studies.

He was a leading Shakespeare scholar, who attracted public attention with the notes he contributed to Dr Johnson’s great edition of Shakespeare (8 volumes, 1765), who paid tribute to his ‘diligence and sagacity’. Steevens was largely responsible for enlarging and revising Johnson’s edition in 1773 (10 vols.) and again in 1778 (10 vols.). After Dr Johnson’s death for many years Steevens collaborated on a friendly basis with the other great Shakespeare editor of this period, Edmond Malone, who published his own edition in 1790 (11 vols.). Feeling slighted by Malone, Steevens produced a new edition in 1793 (15 vols.), remarkably quickly. As a contemporary recorded, ‘he left his house every morning at one o’clock with the Hampstead patrol, and, proceeding without any consideration of the weather or the season, called up the compositor and woke all his devils [workmen]. The nocturnal toil greatly accelerated the printing of the work; as, while the printers slept, the editor was awake; and thus, in less than 20 months, he completed his last splendid edition.’

Steevens certainly possessed ‘astonishing energy’ and perseverance, the more remarkable given the absence of any libraries at that time. He built up his own considerable collection of rare books (sold at auction in 1800 for £2,740), from which he provided hundreds of notes illuminating the most obscure details of Elizabethan language and customs. Unfortunately, he also loved hoaxes. In 1783 he published an article describing the upas tree of Java, which could kill all life within a range of 15 miles, the authority being a completely fictitious Dutch traveller. The unsuspecting Erasmus Darwin admitted the upas tree to his poem, The Loves of the Plants (1789). Steevens contributed to his Shakespeare editions many bawdy notes which he attributed to some of his Hampstead neighbours. A certain ‘Mr Collins of Hampstead’ (unidentified) was credited with a note on Elizabethan beliefs in the aphrodisiac powers of the potato, illustrated with a remarkably wide of quotations. Steevens also wrote a note, expanded in successive editions, on the fact that stewed prunes were used in Elizabethan brothels as an abortifacient, which he ascribed to ‘Amner’. This person actually existed, the Reverend Richard Amner (1737-1803), ‘for many years the Minister of a Dissenting Congregation at Hampstead’, and Steevens would have derived pleasure from the fact that some of Amner’s notes have been unwittingly cited by modern scholars. On the other side, Steevens was praised for his generosity. He helped some people with gifts of money, such as Fuseli and Chatterton’s mother. For others he freely shared his considerable knowledge, helping Charles Burney with his history of music, but also Sir John Hawkins for his rival history. The help he gave Isaac Reed, historian of the drama, and John Nichols, biographer of Hogarth, was so great that he was in effect co-author. He was also a loyal friend, gaining my respect for visiting Dr Johnson on the day of his death.

I have included many selections from Steevens’s work in two volumes of my collection, Shakespeare, The Critical Heritage: Vol. 5, 1765-1774 (1979), and Vol. 6, 1774-1801 (1981).