Racial Justice Building Research Project

Update October 2023

The work of the Racial Justice Group at Hampstead Parish Church includes a history project looking at the sources of funding for the rebuilding of the church in the 1740s. The reasons for undertaking the project are set out on the five posters put up for Black History Month in October 2022. These remain on display in the church and an update poster is to be added this October. We aim to present the final results of our work in a new exhibition in October 2024.

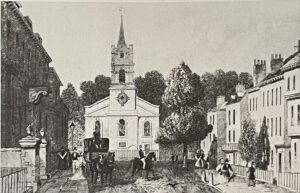

Our present building was consecrated on 8th October 1747 by the Bishop of Llandaff. The Trustees first petitioned Parliament for £2,500 to assist with the rebuilding but were rejected. The budget to rebuild the church was £1750 of which £1000 came from a legacy to the Maryon Wilson family, Lords of the Manor of Hampstead. The rest had to be raised by public subscription.

Initially some fifty persons resident in or connected to the parish agreed to subscribe sums between ten guineas and £50. Eight of them were elected Trustees at a subsequent meeting. The Trustees’ Minute Books form part of the parish records and are available on this website – Hampsteadparishchurch.org.uk/history-and-churchyards/registers-and-records/

The research group are now finding out about the lives and families of these first subscribers (some 200 other subscribers joined subsequently) and what were the sources of their wealth. Did money earned from the transatlantic slave trade form some of the wealth used to build HPC?

Our research methods

Members of the research group have some experience of family history records, and the internet makes historical research much easier. However, we needed to reach out to others who are more familiar with this area of work for their insights and guidance. We organised a trip on 1st April to Lambeth Palace Library to view the exhibition ‘Enslavement: Voices from the Archives’. Letters, books, and documents from the Library collections were displayed to show some of the links between the Church of England and transatlantic chattel slavery. It was useful in the way it showed the arguments put forward using the Church’s teaching, at the time, both for and against the abolition of slavery. Most moving were the two documents from enslaved people themselves, one from New York born Esther Smith who was living in London and attempting to avoid being sent to a plantation in St Christopher in the Caribbean. These are extremely rare; petitioners were threatened with severe punishment for their requests and killing of enslaved people was not considered a crime in many places until well into the 18th century.

Sue also contacted the Legacies of British Slavery Centre (LBS) based at University College London which has its foundations in the Legacies of British Slave-ownership project created in 2009 by Prof. Catherine Hall and colleagues. The website (https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs) was launched in 2013. Initially (2009-12) LBS focused on the people (70,000 in number) who benefited from compensation paid to slave-owners when slavery in the British Caribbean was abolished in 1833-38. The work then extended backwards to look at the Structure and significance of British Caribbean slave-ownership 1763-1833 (2013-2016). Sue met with Keith McClelland, Honorary Senior Research Fellow for the project and he has been appointed as a guide and mentor for our initiative.

The group held two seminars too. In March at London Metropolitan Archives, Senior Archivist, Sally Bevan introduced the work of the LMA and showed us the originals of a number of relevant parish records. July saw a very helpful session at the Parish Rooms with 18th century and Black history specialist, Dr Kathleen Chater, author of Untold Histories: Black People in England and Wales during the period of the British slave trade c1660 – 1807 (Manchester University Press, 2009) sharing her research and answering the group’s queries.

Some initial findings

The team have focussed on the 50 initial subscribers who invested between £10 and £1000. According to the Bank of England, the modern equivalent of a £50 donation in the late 18th century is £10,000 today. The sums listed on the subscribers’ lists for the rebuilding of the church are therefore very large. At the end of the 18th century only around 6 or 7% of the population had an income of £1000 or more per annum. For example, a shoemaker in 1740 averaged an income of £30 per annum. Here is the analysis of the occupations of the 50 subscribers based on what we know to date:-

| Occupation or status | |

| Tradesmen (City of London Livery Company members or local) | 10 |

| Unknown | 12 |

| Farmer | 1 |

| Lawyer | 3 |

| Landed Gentry | 9 |

| Member of Parliament | 1 |

| Lord of the Manor | 1 |

| Widow/spinster | 2 |

| Merchants (Antigua, Russia, East Indies and Virginia tobacco) | 4 |

| Licensed Victuallers | 7 |

| 50 |

Those directly involved in the transatlantic trade were a minority and mostly from the wealthy classes from the gentry up. Our subscribers were well-heeled but many appear to have been local tradesmen or shopkeepers. It will be the landowners and merchants who are most likely to have either owned or had shares in estates using enslaved Africans. Those obviously profiting from slavery in our list are the merchant and City of London ‘Council man’ for Bread Street Ward, Robert Cary (grave XE061) described by The Daily Post, 17 March 1739 as a tobacconist and ‘a very eminent and considerable Virginia Merchant’ and John James ‘of Antigua, merchant’ (grave XE126).

Our research involves tracing not only the occupations of the subscribers but also the origins of any inherited wealth. One example is Coulson Fellowes (1696-1769), a barrister and landowner who became MP for Huntingdonshire in 1741. He appears to have inherited extensive land holdings in Devon and Somerset, likely to have been mainly derived from his mother Mary Martyn, the daughter and heiress of Joseph Martyn (1643-1718), a prominent sugar merchant and London agent for plantation owners in the Leeward Islands. [i]

His father, William Fellowes (1660-1724), was a barrister and was left money (possibly £30k?) in the will of his father-in-law (Joseph Martyn) with a requirement that it should be spent on buying property in Devon for the use of William’s male heirs. Joseph Martyn and William Fellowes both acted as executors in 1703 of the will of Martin Madan, owner of sugar plantations (and slaves) on Nevis.

Coulson’s uncle, Sir John Fellowes (1670-1724), was a Director and Sub-Governor of the South Sea Company and his paternal grandmother (mother of William and John) was Susanna Coulson, heiress of Thomas Coulson MP, a Director of the East India Company.

The first donation to the church rebuilding fund was £1000 from a legacy from the Estate of William Langhorne, a member of the Drapers Company and an East India Company merchant, who became Governor of Madras. However, within six years he was removed for trading illegally on his own account rather than for the East India Company. William and his brother Thomas were Quakers from Westmorland. William purchased the Manor of Hampstead in 1707. Thomas was a merchant trading out of Genoa and had a large estate; William paid an attorney £1,000 to collect the estate for probate. William himself died in 1715 leaving funds to several deserving causes including a hospital in Madras. The Maryon Wilson family inherited Hampstead Manor through his descendants and John Maryon donated £300 to the fund himself.

On page 218 of Park’s Topography & Natural History of Hampstead, it states that when the Church came to be rebuilt the William Langhorne legacy was invested as follows:

| £ | |

| Old South Sea Annuities | 438.13.04 |

| In new annuities | 155.12.01 |

| In South Sea Stock | 37.01.02 |

| Cash being several dividends | 470.00.00 |

| TOTAL | 1101.06.07 |

It would seem that the first £1000 was spent between 1714 and 1744 on talks, fees, Acts of Parliament (an 18th century equivalent of the HS2 project?).

There are only two female subscribers on our list but identifying their histories has its own special challenges. Ann Weyland may be the widow of Mark Weyland, a merchant in the City of London, deceased by 1744. It may be their son, another Mark, whose will was proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury in 1797. There are Weylands with connections to Norwich and Ipswich. Ann Weyland could be the widow of any of them. Mark’s brother John was involved on her behalf after her husband’s death in a Chancery case in connection with the Indian subcontinent. There were other Chancery cases involving a Mark Weyland in 1670 and 1723.

However, John Weyland was married to Ann Sheldon in Tottenham in 1741, so she may be his wife. The brothers may have been business partners and press notices give some clues as to their livelihoods:

London Spy Revived, 3rd March 1738 reports Mark Weyland filled a vacancy in the Court of Assistants of the Russia Merchants. Read’s Weekly Journal or British Gazetteer, 15th April 1738. Mark Weyland was among those chosen a Director of the Bank of England. He was a new member.

And some years later the Penny London Post, 27 February – 1st March 1745 noted ‘On Wednesday died, advanced in Years, at her House in Crutched-Fryars, Mrs. Weyland, Relict of Mark Weyland, Esq; many Years an eminent Italian Merchant of this City’.

The second woman subscriber, Elizabeth Rainge, married twice making it extra tricky to identify her in documents. She was born Elizabeth Hutchinson in 1684 and baptised at St Paul’s, Covent Garden. She married James Rainge (born 1640) in 1709 at St Martin’s in the Fields. They were both living in that parish. James died in 1743 aged 103. She met her second husband, widower John Wishaw, (also a subscriber) in Hampstead. The following marriage notice appeared in the London Evening Post of 11-13 June 1747.

‘On Thursday last was married, by the Rev. Mr. Warren, of Hampstead, John Wishaw, Esq; an eminent Practitioner of the Law, to Mrs. Elizabeth Rainge, of that Place, an agreeable Widow Lady with £15,000 Fortune.’

Both her husbands were lawyers. There are some cases in the Chancery courts with which James Rainge was involved and which concerned the Indian subcontinent. Elizabeth died in Hampstead and was buried at HPC on 10th January 1763.

An example of a man whose career does not appear to have any direct connections to colonial trade is Joseph Stanwix, an attorney. He took a number of apprentices between 1720 and 1735. He had rooms in Bartlett’s’ Buildings, Holborn and seems to have done routine civil cases.

He is mentioned in advertisements acting in connection with:

- the sale of a property in Brompton (Daily Post, 8th April 1727);

- a bankruptcy (London Gazette, 24-28th December 1728);

- the sale of a property in Camberwell (Daily Post, 5th April 1729);

- settling the debts of a man in Newgate prison for debt. (London Gazette, 2nd-5th July 1743)

And the Daily Journal of 8th January 1735 records

‘Last Night the Third Jury for inspecting the Officers of the Court of Chancery, and enquiring into their Fees, met at the Office in Arundel-street. This Jury consists of the following eminent Attornies’. List includes Joseph Stanwix of Bartlets Buildings.

One family involved with Hampstead over several generations is that of John Vincent. There appear to have been three John Vincents in successive generations. Camden History Society graveyard survey (1978) provides information based on grave no. XB164, which is still extant but the inscriptions are almost illegible.

John Vincent Senior (1664-1719):

From Buried in Hampstead: “Had a brewery in the High Street around 1700, and laid water pipes thither from the Cold Bath near Well Road. He also brought the first piped water to other Hampstead residents. He ran Jack Straw’s Castle c 1713. His son rebuilt the brewery in 1720, as the arch next to 9a High Street says. His grandson Robert [1729-86] owned Nos 3-17 High Street, two pubs [now gone] and the pond in Well Road piped water.”[ii]

The Petition to Parliament in 1710 for funding for rebuilding the church (original is in LMA) states that contributions to cover the costs of the procedure were to be deposited with Mr John Vincent. This must have been JV Senior.

John Vincent (1691? – 1755)

This is probably the 1745 subscriber, and the one who rebuilt the brewery in 1720. Unfortunately the inscription on his grave has not survived but the burial register records the burial on 23.07.1755 of “Mr John Vincent Senr, buried in his vault.” There is also a baptism record of “John, son of John and Mary Vincent” on 13.03.1691 which would be around the right date, although the grave refers to the older JV’s wife as Sarah. (Sarah died aged 45 and might have been a second wife.)

This must also be the John Vincent who is referred to in advertisements published in 1744 and 1746 about rewards offered following thefts in Hampstead, suggesting that he would have been the head of an association of local traders who helped with the costs of private prosecutions. His wife Sarah (d.1765 aged 78) is referred to as the “eldest daughter and co-heiress of Richard Cowper of London, gent”.

John Vincent Jnr (1721? – 1754)

John and Sarah had three sons and a daughter: John Junior, d.1754 aged 33, Richard, d.1776 aged 57, Robert, d.1786 aged 57, and Sarah, d.1767 aged 45.

The Burial register for 1754 refers to “John, son of Mr John Vincent, buried in a vault” on 25.03.1754. The gravestone refers to him as “John Vincent jun. 2nd son of the above John Vincent”.

John’s daughter Sarah was married to Lewis Schuman of London, merchant, who died in 1769 and is also buried in the same grave.

Read’s Weekly Journal or British Gazetteer, 23rd March 1754 records “On Monday [18 March] died John Vincent, jun., Brewer at Hamstead [sic].”

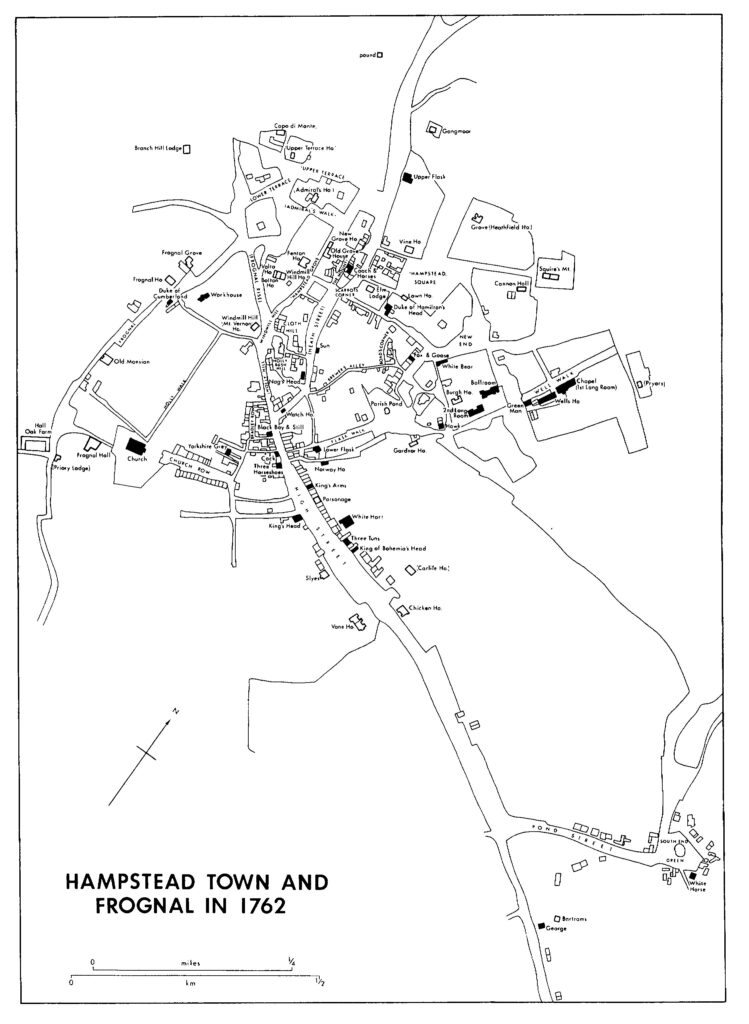

So to end with a few tentative conclusions. It has been interesting to be reminded how different the parish was 300 years ago. It was of course not part of London but situated in rural Middlesex with a few farms and large estates and clusters of shops, public houses and homes along a limited number of roads. Many of our subscribers did not live in their houses here all year round and were based elsewhere. Hampstead was very much somewhere to escape the hurly burly of city life.

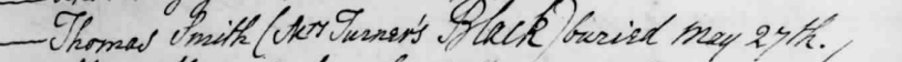

It seems likely that only a small number of our subscribers and their families had trading connections with the Americas and the Caribbean. It is more likely that there is a concentration of people with connections to the East India Company. But we have more research to undertake including tracking wills, possibly examining Chancery records and looking for links to those who were compensated after the abolition of slavery. We are aware of the contribution of local residents to the cause of Abolition. For example, William Davy, Sergeant at Law defended a runaway slave against the claims of a slave owner. But we have also come across a reference in an HPC Burial Register to someone who had been or was still an enslaved person. He is referred to as “Thomas Smith, Mrs Turner’s Black”. [iii] John Turner gave £50 to the rebuilding fund. The trade in enslaved Africans was seen by most people pre-Abolition as perfectly ordinary and merely part of being a global power.

Sue Kirby

Research by Inigo Woolf, Judy East, Nicholas Walser, Peter Ginnings and Dr Kathy Chater.

[i] Joseph Martyn by John Smith after Michael Dahl mezzotint 1719

A prominent sugar merchant and London agent for plantation owners in the Leeward Islands, Joseph was grandfather to church building fund subscriber Coulson Fellowes.

Copyright National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG D38301)

[ii] Photograph Nicholas Walser

[iii] From the Burial Register of Hampstead Parish Church 27th May 1761. Available on this website – Hampsteadparishchurch.org.uk/history-and-churchyards/registers-and-records/

.