St John at Hampstead

2 June 2024

Mark 2: 23-3:16

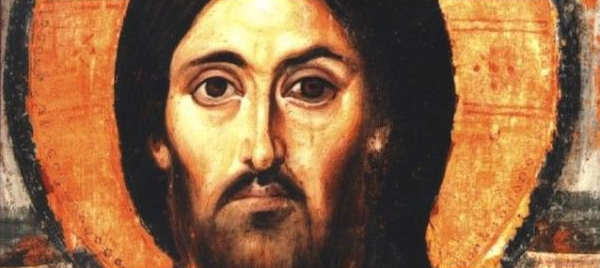

There’s an icon of Christ that you may have encountered

and which I added the service booklet this week. It can a

bit disorienting, a bit confusing, in fact you might say

there is something wrong with it. The icon is known as the

Christ of Mercy and Judgement. It’s a little bit like an

optical illusion. Here’s how it works. If you place your

palm covering one side of the face of Christ, you will be

regarded with an eye that seems to be full of mercy. Switch

your hand to the other side and you see an expression of

judgement. It’s an image that can be a bit uncomfortable,

maybe even troubling, until we learn to sit with both sides

of the face of Christ.

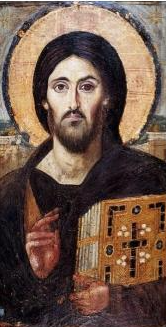

It might be helpful to think about this icon as we explore

the balance between judgment and mercy, resulting from

two actions of Jesus and his disciples.

Jesus and his followers seem to have deliberately placed

themselves into conflict with the Pharisees which provoke

words of judgement. The disciples did not need to pluck

the heads of the grain and nibble at them. While it is the

kind of thing any of us might do while idly walking along

the edge of a cornfield, it could almost be seen as a

provocative move, especially if they knew they were being

observed. Then Jesus performs an act of mercy by openly

heals a man with a withered hand, in the synagogue, where

he can be absolutely sure that he is under surveillance. We

are at the very beginning of St Mark’s account of Jesus’s

ministry and already we are seeing a glimpse of the stern

eye from the icon of mercy and judgement.

It is of course easy to take examples like these and use

them to emphasise Jesus’s radical ministry, to say that he is

attacking the rules. But Jesus lived and died an observant

and faithful Jewish man, and as he says in St Matthew’s

Gospel account—‘do not think that I have come to abolish the

law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfil’. If we

seek to understand him—to follow him—we will need to

think a little more deeply as to what is happening in this

gospel reading.

Yes, there is a sense of things being challenged, held up to

the light, examined closely to find the real motivations

behind the law. Sabbath is a very significant practice, it

has real cultural value and it is deeply linked to Jewish

identity. Jesus never rejects the idea that the sabbath is

anything but significant. Instead he is challenging the

notion of what work might mean on this special day.

Sabbath points towards life and love—it was given by God

as a time of rest, refreshment and for the flourishing of

family life. It is linked to holiness and to the very goodness

of creation. It also carries within it the echoes of liberation

from slavery. In saying that the sabbath was made for—

gifted to—human beings, rather than the other way

around, then perhaps in this context what Jesus is actually

doing is calling for a restoration of the true, the original

meaning and purpose of Sabbath.

We see the stakes rise as the Pharisees continue to watch

him. Having wandered through the field he is now in the

synagogue under full scrutiny. And he does what he must,

what he was born to do—he heals. He takes the withered

hand of a man and in healing it he sets him free. Free to

wander through a field and pluck the heads of corn if that

is his wish. Jesus recreates in this man the ability to hold,

to grasp, and to raise his hands in a prayer of thanks to

God for his healing. But this cannot be seen by his those

who scrutinise Jesus—and so the eye of mercy which has

gazed with compassion on the man to be healed, is now

turned to anger and judgement.

It’s a real challenge to us all, because it prompts us to ask a

question of ourselves. Is anything that we do making us

inaccessible or remote from those who might want to hear

and experience the love of God? Can we do more to make

others feel welcome, or to offer a hand of friendship? Can

we be certain that we are not offering a narrow version of

the wide and abundant love of God? Can we devote mental

space to developing our life in God? Can we set aside time

to get to know God better?

What do we do with our day of rest—our Sabbath. In my

life time alone, the notion of a day off has begun to slip

away, with zero contract hours and the gig economy. Not

having a ring-fenced day of rest poses its challenges to us.

When and where do we stop and hold the whole of our life

before God? How do we save a time for just pure

enjoyment with friends and family? How does the so-called

flexibility of everyone having a different day off help us to

build up a common life with friends and family?

These are questions that we all struggle with—whether we

are Christians or not. But when God created the Sabbath,

he meant that it would be a time of rest and joy. It may be

that the whole idea of a Sabbath is now itself

countercultural. In a world that expects us to be constantly

available, it can tempting to equate being ‘busy’ with our

own self-worth.

Mercy is balanced with judgement in the eye of the icon of

Christ. I believe that the gaze of mercy says to each of us

—‘Come and sit with me, let me take your hand and tell you how

much I love you, how much I understand that every day you try to

do good. Let me assure you that I know this, let me invite you to

just rest a little while with me’.

In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy

Spirit.