Readings: OT: Daniel 10:4-14; NT: Revelation 5:1-10

Between the words that are spoken and the words that are heard, may the Holy Spirit be present. Amen.

When Mthr Carol very generously invited me to preach, the theme which spontaneously came to mind to partner with ‘faith’ was ‘imagination.’ It was necessarily ‘imagination:’ from my upbringing and how faith was portrayed to me throughout, to my love of the arts, imagination has played a significant part in my faith. This is true not only as we understand ‘imagination’ as a capacity to form for oneself images or representations – something that Christianity has prompted from its early centuries, the Church, worldwide, being one of the greatest art commissioners throughout the ages, whilst having an ambiguous relationship with images – but also true as we understand imagination as the capacity to conceive ways of behaving, of being with one another, which, if we take it at heart, are counter-cultural, counter-intuitive, challenging limits, hierarchies, exclusion over and over again when placing God, the source of a daring and genuine love, at the centre.

And it is this particular kind of imagination, rooted in faith, that I’d like for us to prayerfully consider tonight.

Before we do: just a trigger warning that this sermon will refer to wars, war camps and while it won’t give any graphic detail some of us may find it distressing.

‘Unbelievable – but true.’

In February 1942, Singapore was taken by the Japanese forces who found themselves with way more prisoners than they had anticipated. Within a few days, civilians as well as members of the Armed Forces were sent to a camp named Changi and dozens of thousands ended up being packed within an area built for a few hundreds. The sanitary conditions were dreadful, and diseases quickly spread like wildfire. Photography was very limited and carefully controlled for propaganda purposes.

However, there were painters among the prisoners.

Charles Thrale was one of them, and quite a prolific one. Along with him were others like Ronald Searle, with whom some of you may be familiar, or Philip Meninsky – just to name a few. They kept on drawing or painting what they saw around themselves – the beautiful and the ugly, the heart-breaking and the inspiring, despair, death, life. Those drawings gained crucial value after the war during the War Criminal Trials held in Tokyo from 1946 until 1948. The drawings and paintings became evidence of crimes committed in the camps. They led to death sentences or life-imprisonment.

After the Liberation, some artists started to exhibit their drawings, such as Ronald Searle, in Cambridge.

On a much wider scale, as early as January 1946, an exhibition opened in London which would tour in the UK for 18 years, visiting a 135 principal cities and towns. This one showed the works of Charles Thrale.

His drawings and watercolours depicted the conditions of the prisoners in the camps and included a fair number of portraits of fellow prisoners – British or of the Allied Forces – as well as Japanese or Sikhs guards, and some local people: Chinese, Malay, mostly.

From Cheltenham to Bristol, Cardiff to Birmingham, Hereford, Bournemouth, Oxford, Cambridge, to Liverpool, York, Skegness … the exhibition gathered dozens of thousands of visitors – many former Prisoners of War, members of their family, along with national and international visitors.

Life in the camp was unimaginable, and former POWs had been short of words to describe it to their families and friends. Those who had lost loved ones in the camps, expressed their gratitude for the artist for giving them a glimpse of what it was like – for the visual aid or a window into an experience which went beyond words.

‘Unbelievable – but true’ was a comment left by a visitor in one of the many Exhibition Comment Books. The person, who was likely a former Prisoner of War, captured the sentiment of many who returned from the war. What could not be imagined was right in front of the visitors’ eyes.

‘Very true’, ‘this is exactly how it was’ several former prisoners commented.

Along with the trauma – and what was later coined as the ‘Changi memory’ (or rather amnesia) – there was the fear of not being believed by loved ones, thus being left alone in that memory if one attempted to share it. It went beyond where one would venture one’s imagination.

Yet, not all captive artists painted what they witnessed. One in particular decided instead to stretch out the imagination, and in a radically different direction.

His name was Stanley Warren. He had been very sick with dysentery and renal disorder and was put in the hospital in Changi. While convalescing, he heard fellow prisoners singing hymns in the chapel which they had built on the ground floor of his ward. The Chapel was named after St Luke, the physician. One day, Warren was approached by Padre Chambers, the Priest, who had heard that Warren was an artist. Chambers asked him if he would consider painting murals in that chapel. Warren accepted and settled on a series of four which would represent Jesus’ life. A fifth one was particularly requested by the Padre and would represent St Luke among the prisoners.

Warren began each painting with a biblical verse which he would write on the mural itself. The series contained the Nativity, the Last Supper, the Crucifixion, and the Ascension. And each, of course, had a particular resonance with the prisoners’ situation.

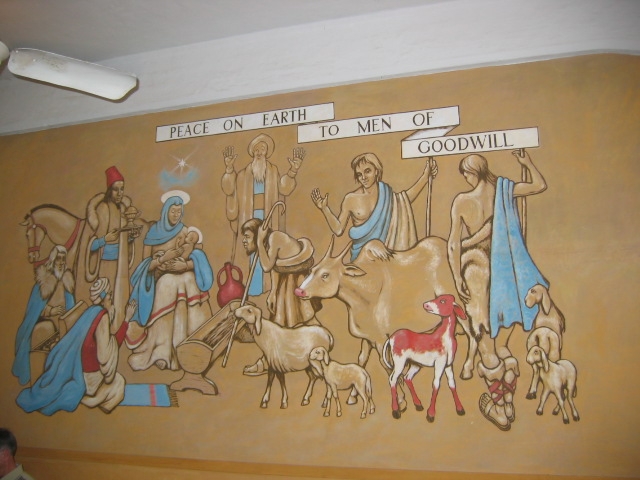

Two in particular, I think, must have stretched the captives’ imagination. The first, which led to a disagreement between the Padre and Warren, was the Nativity – this is the painting of which you have a copy. The biblical verse came from Luke 2:14 which Warren had selected in the King James Bible: ‘Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men.’ But the Padre requested another version, closer to the NRSV: ‘peace on earth to men of goodwill.’

The second was the Crucifixion, for which Warren chose Luke 23:34 ‘Father, forgive them. They know not what they do.’

If you are a regular Church goer, you will have heard these verses over and over again. If you have been to Coventry, you will have seen the passage from Luke 23 inscribed on a wall where a Cathedral once stood.

But to get a little sense of what Warren was doing, we have to stretch our imagination and involve our bodies and our hearts. In the midst of horror and excruciating suffering, Warren represented what must have sounded simply unthinkable to many. Or worse still: unimaginable.

How could anyone forgive the treatment received in the camp? How could anyone wish peace and good will toward all humans?

I was not raised Christian. I was raised atheist. I was raised atheist in one of those regions in the north of France where both World Wars have left scars visible to this day. As a child, I played in trenches covered with bluebells and lilies of the valley. I played among unexploded shells and buried wooden huts which had served for coded transmission, but which nature had finally reclaimed as hers.

To cut a long story short, my entry point to the Church was choral Evensong in an Oxford Chapel where snippets of the Book of Revelation were read every single evening. While the beauty of services would make my heart particularly receptive, what it taught me, night after night, was that this faith requested an engaged imagination, required of us to ask questions, to investigate, to make room for nuances and ambiguity, and refrain from seeking an immediate answer.

Both our passages from Daniel and Revelation demand this of us tonight. From the man whose body ‘was like beryl, his face like lightning, his eyes like flaming torches, his arms and legs like the gleam of burnished bronze’ to John telling us of the scroll sealed with seven seals and the four living creatures and the Lamb having seven horns and seven eyes, surrounded by harps and bowls full of incense – our whole body is invited to imagine what this may look like and feel like and smell like.

By contrast, one had to guard oneself from the imagination mentioned in the Magnificat: ‘He hath scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts.’ Instead, the desirable imagination had to be rooted in God, re-wired in God, in love, and used for the benefit of all, for good towards all. But even imagination has its limits.

‘Unbelievable – but true’

What our faith teaches us is that where we think there is no way, that we cannot imagine one, it does not mean that it is impossible. Faith teaches us that even in the worst situations God is present. It is a faith that teaches us that when imagination fails faith comes in to lead us and sustain us and support us. ‘I cannot imagine it’ does not mean that it is not possible nor that it is not true. My limitations are not God’s limitations or else I make a God after my own image.

I am French and it would be unimaginable for me to feel hatred against Germans. But this would have likely been hardly imaginable for my grandparents and past generations for whom simply hearing German provoked an immediate tension in their body, prompted traumatic memories, and triggered anxiety if not worse.

When I think of the atrocities committed in Ukraine and in Gaza, of the death of captives held by Hamas, the unfathomable suffering of children from their day of birth, I cannot conceive how reconciliation and peace will ever be possible. Especially after living in Jerusalem and seeing what actually happens – not relayed by online images which I trust less and less in this time of AI. When I think of what we have inherited from the trans-Atlantic slave trade, as well as what has been forgotten in our lands regarding slavery, when I think of Martin Luther King Jr and his dream of Beloved Community, yet being shot dead, my imagination runs dry.

Yet, because this is my faith, I have faith that peace and justice can happen and will happen.

The Comment Books from the Thrale Exhibition recorded an evolution of the comments which could easily bring one to tears. Initially filled with anger, racism and hatred against Japanese in the immediate post-war period, nurturing the desire of vengeance and equal suffering, the comments about seeking reconciliation and understanding gradually and overwhelmingly outnumbered the former. They highlighted the importance of a fairer assessment of the wider picture, the role that all countries played in that war and the importance of building new relationships through younger generations of many nations.

The seeds of peace and reconciliation are there as early as in the first exhibition. In fact, they are there in Warren’s paintings in Changi, as well as in Thrale’s, Searle’s and Meninky’s who not only captured the conditions of the captives, but also the beautiful gestures of some guards, sometimes risking their lives for the prisoners. Glimpses of God’s presence throughout.

And so, when we feel hopeless, when we despair of one another and of the state of the world, it is precisely when faith comes in. When it feels impossible to imagine a way out, to imagine how a situation could improve, faith may become the only resource left to help us move ahead by giving it all out to God to continue to walk, with trust, even if we cannot see where this will lead us – by faith and not by sight.

Unimaginable – but true.

Amen

© RAFSA Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore